Empty Liverpool: Time for a little joined-up thinking?

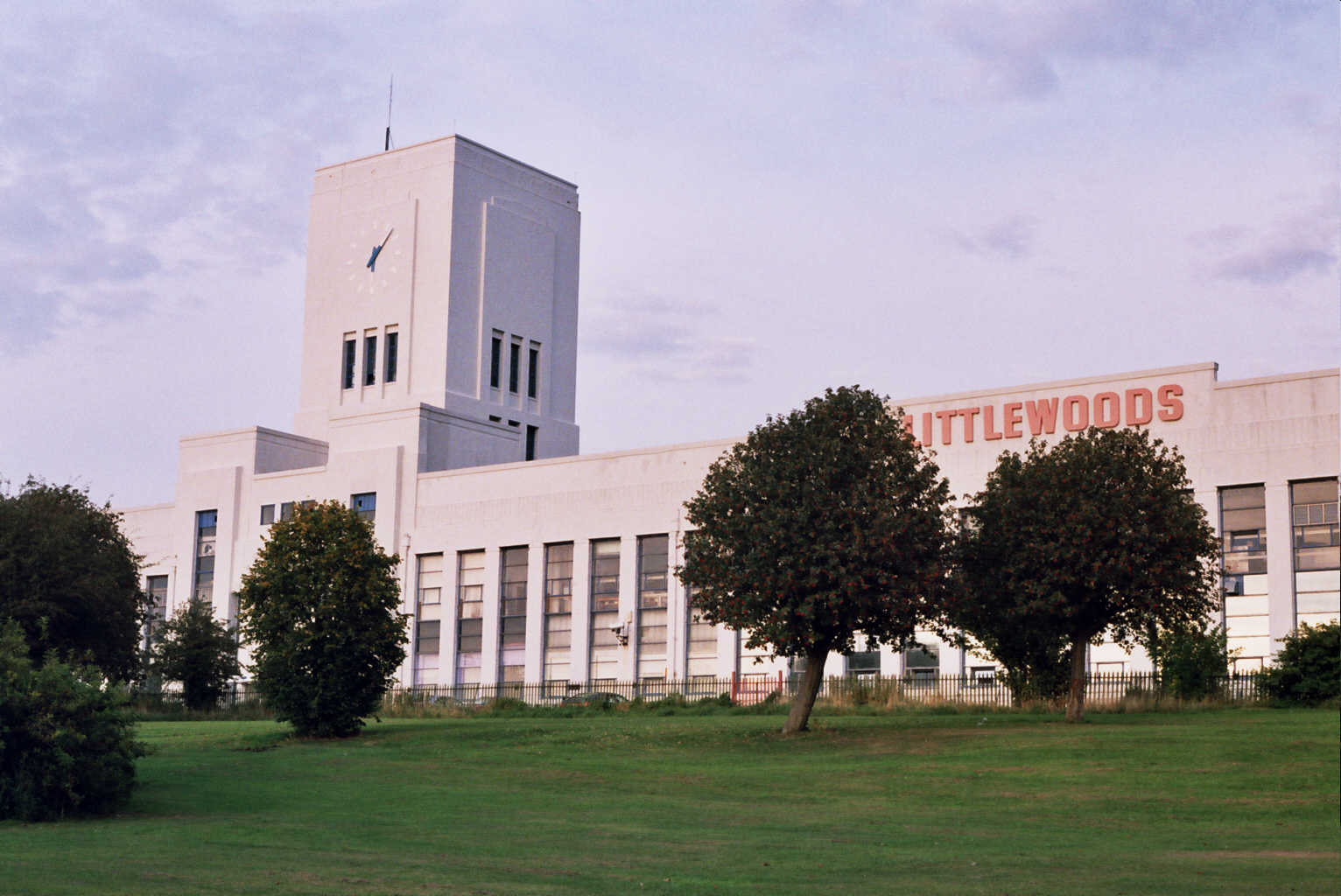

Looks like plans to resurrect the old Littlewoods building on Edge Lane have hit some turbulence. The striking Art Deco-inspired pile had originally been earmarked for the Urban Splash treatment. Then, when that failed, Manchester based Capital and Centric stepped in, with Liverpool Council backing, to create a new mixed-use scheme of hotel, shops, offices and business units.

“The Littlewoods Project is a big challenge, but where others saw problems, we saw opportunities. When others struggled with viability we found vitality,” Capital and Centric say on their website.

SevenStreets understands that, for now, that dream is on hold - despite the council still striving to find a solution.

We’ve talked before about the city’s real need to tackle its empty buildings (and Placed launched their sparky Hidden project following our feature). But there are empty buildings and empty buildings. Changing a city centre office block into student flats is one thing. But what do you do with 250,000 sq feet - especially when a 430,000 sq ft retail park, just up the road, is still ghost-box central?

One way out, perhaps, is to think a little differently. Think of these sleeping giants not as empty boxes, but as future biospheres. Nascent galaxies with the potential to become centres of gravity for an entirely new ecosystem.

The Argonaut building in Detroit shares many similarities with our Littlewoods building. Both Art Deco styled former hives of industry, both deserted sometime in the 80s. Both sharing a great bone structure, and deep affection in their cities’ hearts.

But here’s where the stories diverge. Today the Argonaut is, most definitely, alive. Its ten stories are home to a thriving colony - not of student flats, nor Sainsbury’s supermarkets. But of a holistic, entrepreneurial, private-enterprise-focussed community.

Today, the Argonaut is the Taubman Center for Design Education. Within, a small company called Shinola produces bicycles (similar to the wonderful Liverpool Sparrow Bike Company, who toil under a leaky roof), and another creates high-end watches. Above Shinola, Detroit’s College for Creative Studies readies undergraduates for the real world. Students learn, graduates make, punters buy. A critical mass, all under the same roof.

Across Detroit, huge, once-empty buildings are being recolonized. But not with student flats. With growing industry. Over 10,000 new jobs have materialised in these ghostly ex-banking offices and automotive HQs. The city’s empty buildings aren’t seen merely as spaces to fill, but opportunities to create what’s known as intellectual spillovers - “spaces encouraging one company or person to learn from another company or person”. To create momentum. Not Morrisons.

Thirty-seven percent of the jobs (about 120,000) in the city of Detroit are in these new, tightly connected neighbourhoods, comprised almost exclusively of super-sized old office blocks and industrial units (taking up only three percent of the city’s land). But all of Detroit benefits: by creating jobs, drawing in residents, and generating tax revenue and economic uplift for a city that is greatly in need of it. Like us.

We’ve dabbled, of course. The Wavertree based Liverpool Tech Park isn’t short of dazzling SMEs, but it’s a soulless place, with less restaurants and bars than at the South Pole (this is true). I’ve not yet interviewed anyone on campus who actually likes it there.

Imagine if the Littlewoods building became a campus-cum-incubator space. A place that didn’t feel quite so windblown and edgelands, but the heart of a real, vibrant community? What if we engaged in a little joined-up thinking, instead of parachuting in one-size-fits-all solutions of supermarkets and shit flats?

What if we got the city’s 30 fastest growing companies in a room and asked them: what do you ship in? What could we build here? What skills do you need next-door? How can we keep more of every pound in our local economy?

For every £1 spent at a chain supermarket, only 10-12p stays in the local economy. Imagine if our specialist engineering needs, our bread, our printing, or lab equipment and our printed circuit boards were made here?

If we look at what’s already thriving in a place, and work towards adding to it, rather than resorting to highest-bidder sell-outs maybe, just maybe, we’ll have real regeneration. Not fast-food regeneration, that leaves us malnourished a couple of years down the road.

“Public policies at regional and local levels have for several decades favored corporations and investors over local enterprises and ownership,” says the New Economy Working Group. “In the name of attracting jobs, many local businesses that have served their communities for generations are driven out of business by subsidized big box stores. Local manufacturers find themselves competing with foreign producers that pay their workers pennies an hour.”

You and I know it as the Cllr Kennedy-lauded Project Jennifer effect.

Barcelona did it with its 22@ Districte de la innovació. The city colonised 500 acres of disused industrial plots, and down-at-heel neighbourhoods, and encouraged a mixed-use model of businesses, housing, university campuses and start-up spaces. So far, 4,500 firms have located in the area, many supplying the skills and widgets for their neighbours. It’s been so successful Boston, Malmo and Cape Town are following their lead.

Barcelona realised that innovation and a thriving community - a community with a viable future - are symbiotically linked. They both need each other to grow. That huge supermarkets are more pancetta than panacea.

Already, the city is witnessing the beginnings of an automotive supply chain feeding the hungry Land Rover plant. But we should be looking around at where else growth might come: digital? Life sciences? Creative industries? Specialist engineering? Catering? Hospitality? Transportation costs alone can total as much as 25% of the product’s selling price. In other words, a quarter of a start up’s total revenue may be spent on transportation expenses for raw materials.

It’s no surprise that key multinationals in every major industry, from automobiles to mobile phones, are developing centre-of-gravity supply chains in their major markets.

We should plan to encourage a colony of companies that feed off each other. It’s encouraging to see the Studio School opening in The Baltic - brilliant new thinking from the North Liverpool Academy Trust offering cutting-edge facilities for students in life sciences and digital gaming technology.

But we need more. Much more. And we’re not short of big empty buildings.

We all know the benefits pop-up retails gives landlords, and try-out traders. But imagine Littlewoods as factory floor - creating fashion and accessories - and marketplace? The location is perfect. And we have the talent here.

While the cost of transmitting information across continents has fallen, the cost of transmitting knowledge, labour, parts and services still rises with distance. Therefore, the spillover benefits of clustering, especially for high-value, knowledge intensive sectors, is potentially huge.

Liverpool punches way above its weight for its knowledge-intensive output. We need to build hubs that work smarter. We need to see our empty warehouses and brown-field sites as future mini cities, toiling towards a common goal. Neural networks, thrumming with possibilities.

According to Jennifer Bradley and Bruce Katz, writing in the New Republic: “Researcher Gerry Carlino has found that the number of patents per capita increases, on average, by 20 to 30 percent for every doubling of employment density,” and that intellectual spillovers drop off dramatically with distance.

“At a distance of just over a mile, the power of intellectual ferment to create another new firm or even another new job drops to one-tenth or less of what it is closer in. Researchers at Harvard Medical School have found that even working in the same building on an academic medical campus makes a difference for scientific breakthroughs. As one of them explains, “Otherwise it’s really out of sight, out of mind.”

The finite resources of our city council really requires some concentrated thinking. Where can they spend wisely, to offer the most return? Perhaps targeting resources towards ecosystems that will see exponential benefits is the place to start.

“Interlinking living enterprises form the building blocks of prosperous locally rooted, self-reliant, regional economies. This will give us shared prosperity, and living democracy,” says the New Economy Working Group.

So, again, we’re left wondering. Has Sainsbury’s really found the answer we’re looking for, or has it been right under our noses all along?

-

Charlie Shoes

-

Philip Stratford

-

david_lloyd

-

Conway

-

david_lloyd

-

asenseofplace

-

david_lloyd

-

Peter C

-

Jack Rollinson

-

Guest

-

Jay Martin

-

david_lloyd

-

david_lloyd

-

Kenn

-

James Hawkins

-

Rich

-

Kiron Reid