Liverpool Ghost Streets 3: Manesty’s Lane

Continuing our sometime chronicling of the city's less celebrated streets, David Lloyd unearths a tiny lane with a history out of all proportion to its size...

The Joan Rivers of Liverpool streets, Manesty’s Lane has been surgically enhanced, bent out of whack, and plastered in so much cover-up that even its closest relatives would be hard pressed to name it in a line up.

Yet, despite its shiny new role as Liverpool ONE’s boutique catwalk no amount of nipping and tucking can airbrush over Manesty’s Lane’s dark and decidedly unglamorous past.

For this sinuous little route has shaped our city’s history more than most - and the Manesty’s Lane that links Flannels to Paradise Street is a mere perky interloper. In fact, it’s not Manesty’s Lane at all.

With the arrival of Liverpool ONE, the city’s tectonic plates shifted the narrow streets that burrowed their way between Paradise Street and Hanover Street. But remnants remain.

To find the source of Manesty’s Lane you have to backtrack to Hanover Street. Here, at Hanover Galleries (current home of the Chocolate Cellar) you’ll find what’s left of its original route, snaking behind the 18th century warehouses.

To find the source of Manesty’s Lane you have to backtrack to Hanover Street. Here, at Hanover Galleries (current home of the Chocolate Cellar) you’ll find what’s left of its original route, snaking behind the 18th century warehouses.

But wander just a few meters down its length and the road, squeezed between the steel skeletons of Liverpool ONE’s service buildings, disappears underground to meet the Q Park emergency access route. It springs back to the surface, like some subterranean water course, just outside the entrance to Waterstones.

From here on, developers Grosvenor contorted the lane, twisting it through 90 degrees so that shoppers entering Paradise Street would catch a sudden, surprising glimpse of the Liver Buildings in the distance. The idea was to ‘link the city with the waterfront’.

Ironically enough, the real Manesty’s Lane is linked to the waterfront in a far more fundamental way. The Street was named after John Manesty, owner of a fleet of slave ships, including the notorious African, responsible for transporting thousands of slaves in the ‘triangle trade’ linking our city to Africa and the West Indies.

But this was no random civic gesture - the street was the site of Manesty’s actual home: by all accounts a grand villa, noted for its fine lavender shrubs. Nice.

But this was no random civic gesture - the street was the site of Manesty’s actual home: by all accounts a grand villa, noted for its fine lavender shrubs. Nice.

The man was the subject of a couple of volumes’ worth of lurid tales, John Manesty, The Liverpool Merchant, published in 1814. You can read them here if you’ve no paint drying.

The books were no hagiography. Author William Maggin, paints an unflattering portrait of his subject:

Mr. Manesty’s countenance was cold; seldom, if ever, relaxing into a smile. His massive head, rapidly inclining to be bald, was firmly set on a pair of ample shoulders. His dress, which never varied, was of snuff-brown broadcloth and a close-fitting pail of breeches, not reaching much beyond the knee.

He’d no doubt have been a regular at Flannels, then.

Maggin spares no punches when describing our city, either:

“However it may shock the fine feelings of the existing race of the men philosophizing by the side of the Mersey, its prosperity had beyond question its origin in the slave-trade, of which Liverpool, having filched that commerce from Bristol, became the great emporium. It is undeniable that many honourable and upright men were engaged in this man-traffic, the propriety of which they never doubted; and that few of the most unexceptionable merchants in Liverpool, though closing their eyes to what was called ” the horrors of the middle passage,” refused to accept the profits which it returned.

The ‘man-traffic’ saw Liverpool grow rich - and one of its chief industries was the refining of sugar. Once a rare and precious commodity it was the slave trade which created a boon in sugar refining.

The ‘man-traffic’ saw Liverpool grow rich - and one of its chief industries was the refining of sugar. Once a rare and precious commodity it was the slave trade which created a boon in sugar refining.

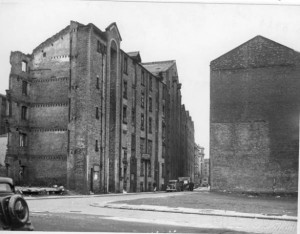

At the beginning of the 19th century John Wright & Co ran a small sugar refinery in Manesty’s Lane - one of about a dozen in the city - the warehouses still remain (pic above). But it wasn’t until Henry Tate, a successful Liverpool grocer with a store next door to Wright’s, joined the firm in 1859 that the business really took off - Tate developed a more efficient production method allowing for refining on a much larger scale. And we all know what happened next in that particular tale.

The lane was also home to one of Liverpool’s first public schools - the Manesty Lane School opened in 1792 - just 70 years after neighbouring Bluecoat school opened up on College Lane - and closed sometime in the 1930s.

Slaves, sugar, schools and shops - an incident-crammed history, then, for a narrow, hidden and mangled stretch of carriageway.

But if Woolton councillor Barbara Mace had got her way a few years back, the street would have disappeared off the map altogether. Mace’s big idea was to rid the city of any streets with names associated with the slave trade.

But if Woolton councillor Barbara Mace had got her way a few years back, the street would have disappeared off the map altogether. Mace’s big idea was to rid the city of any streets with names associated with the slave trade.

“I want the city council to resolve that all streets, squares and public places named after those involved in promoting or profiteering from the slave trade be renamed, and substituted with new names celebrating those who represent diversity and the contemporary challenge of racial harmony,” she said at the time.

Her plan was approved by head of Liverpool City Council, Joe Anderson, who suggested Exchange Flags could be re-named Independent Square.

It never happened. Wisely, we think. For behind the coffee shop fascias and the Fred Perry window displays this curious street - and its name - will always link us to our past. And you know what they say about those who forget their history.

Nice piece. And I agree, re-naming the streets connected with the slave trade is a bad idea. It covers up history, you should ackowledge your past, even if it’s a dark one, although I appreciate the sentiment behind what they were trying to do.

Here’s a bit of Manestys Lane info that you missed off, it also played and interesting role in our pharmacutical industry, which, like sugar started in that area, and here’s a firm that still bears its name:

http://www.oystar.manesty.com/3335.html

Cheers KT. Just shows you, you only gotta scratch the surface and all that history stuff oozes all over your fingers.