Halls of Resistance: Student City

Close to ten thousand new student beds are being built in the city - run by private companies with little or no control over their residents. Should we be concerned that Hope Street is next in their sights? David Lloyd reports.

Wave goodbye to Hope Street. The character of the ‘greatest street in the UK’ (according to the 2012 Urbanism Awards) could be irrevocably altered if the Maghull Group’s Falconer Chester Hall-designed new ‘Student Castle’ gets the go ahead at the council’s Planning Committee hearing next month (pic above).

At least, that’s the fear of local residents - who’ve expressed their concern over the mooted 350-flat student accommodation, opposite the Grade II-star Philharmonic pub, in the heart of the Rodney Street Conservation Area.

“We are already significantly outnumbered by the student population,” a Spokesperson from the local residents told SevenStreets. “Regrettably, this imbalance can have a deleterious effect on the environment in terms of noise at night, which is already the focus of considerable unease, and with respect to littering, broken glass and other forms of nuisance. To add several hundred more residents, many of whom will almost certainly have similar lifestyles will further detract from the quality of life in this location.”

The proposal, slated to rise from the rubble of Josephine Butler house (after Maghull’s previously trumpeted Skybar scheme, gleefully approved by planners, fell unceremoniously to earth a few years ago) has angered local residents and the Rodney Street Association, who’ve expressed concern that this intervention will, like some implanted cell, alter the character of one of the city’s great streets for good.

“This area was not long ago designated the “Cultural Quarter” by Liverpool City Council,” the Spokesperson adds. “It might have been expected that any new building would be of a high architectural standard and would have an external appearance that enabled it to be a welcome addition to the existing buildings on Hope Street. On the contrary, the proposed building is of no architectural merit whatsoever.”

“This area was not long ago designated the “Cultural Quarter” by Liverpool City Council,” the Spokesperson adds. “It might have been expected that any new building would be of a high architectural standard and would have an external appearance that enabled it to be a welcome addition to the existing buildings on Hope Street. On the contrary, the proposed building is of no architectural merit whatsoever.”

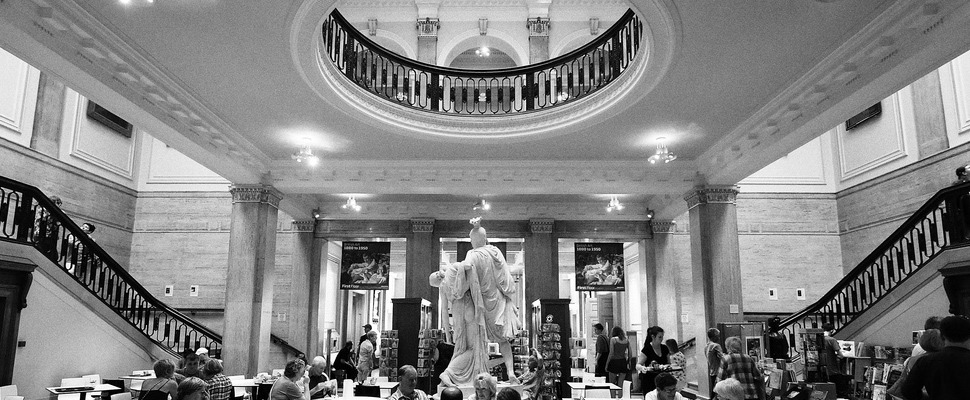

Student Halls aren’t known for their architectural élan - nor our Council for its sympathetic assessment of their impact. After spending £20million on the Lime Street gateway, it approved the ugly halls on Skelhorne Street - the picture opposite is not of some interior detail, but of the facade that faces the street.

Student Halls aren’t known for their architectural élan - nor our Council for its sympathetic assessment of their impact. After spending £20million on the Lime Street gateway, it approved the ugly halls on Skelhorne Street - the picture opposite is not of some interior detail, but of the facade that faces the street.

The residents of the 63 apartments in the adjoining Symphony building - together with stakeholders claim that the removal of the existing trees will be a major loss to the look and feel of the street, with the Philharmonic Pub and Philharmonic Hall benefiting from the only trees in the area.

But are they right?

There is no doubt, private student halls are this decade’s executive loft apartment. Take a look around - there’s a development gold rush going on, every bit as fervent as the apartment boom of the early noughties.

Venerable buildings from Cheapside’s Bridewell to the Tinlings Building on Victoria Street, St Andrew’s Church on Rodney Street to Alsop on Brownlow Hill are being feverishly recommissioned into high-density bed banks for high-churn residents.

Next year, a 710 bedroom complex will open up on Myrtle Street - but it’s the accommodation’s creep into the residential neighbourhoods of the city centre that’s causing most concern.

Unlike the apartments, many of these student halls aren’t being speculatively built: they’re the result of a tender process put out by Liverpool University and LJMU - with the highest bidder winning a contract to ensure a fresh supply of freshmen every term.

SevenStreets understands that the University is planning to close all of its Carnatic Halls in South Liverpool, and the University readily admits that they’re increasingly turning to privately run schemes. There is sound economics behind it: by entering into a partnership with private providers they’re finding a whole new revenue stream (handy, when university admissions are falling).

“We’re keen to ensure that the student experience offered at Liverpool is first-rate and recent market research indicates that in order to attract the best students, we need to offer more accommodation at our city centre campus,” they told us (we’ll be speaking to them, in depth, next week).

But what of the bigger picture? Liverpool currently welcomes 55,000 students to its academic institutions: What if they all want to move in? Will supply always match demand? What controls are being put in place?

Liverpool’s new Head of Planning, the newly arrived Grant Butterworth admits this new wave of city centre student halls comes with its own set of challenges.

“In many cities with growing universities there’s been increasing levels of concern expressed by local communities about the impact of students living nearby,” he says, adding that while most students are ‘well behaved’ complaints range from noise nuisance to a lowering of environmental quality, the viability of local community facilities and the undermining of stable residential communities.

We nod. We reel off a list of similar complaints - from friends living hugger-mugger with student halls along Cheapside’s Victoria Halls. Of wing-mirrors snapped, cars with footprints (and dents) over the roof, freshly deposited piles of sick, and Swedish House Mafia at 3 in the morning (on a Tuesday?).

Anecdotal perhaps, but antisocial, definitely.

Complaints to management, we tell him, have been roundly ignored. Not a single email answered.

When a privately run student hall, put out to tender by a university, and built by a local developer leaves a trail of devastation and sleep-deprivation in its wake - who you gonna call? In our experience, it doesn’t really matter, the buck just keeps on getting passed.

“It’s important that any impacts are anticipated,” Grant says. “Planning control is only one of a suite of powers available to local authorities. The ability for councils, or the Police, to take action under Environmental Health or Public Protection legislation is always there.”

But it’s exactly this fuzzy no-man’s land of accountability that leads to unrest, and to the understandable objections from residents. Surely the problem lies further upstream - in the halls getting planning approval in the first place?

“But planning is concerned with appropriate land use, not the different characteristics of individuals or groups,” Grant says.

In other words, if a location is suitable for families, it’s suitable for students?

“Yes,” Grant says, “Generally speaking, we can’t control or dictate the type of accommodation provided.”

“The default position of the Government’s recent Policy Guidance is to approve new development proposals unless there are impacts which would justify refusing it,” he says.

There are some room for manoeuver -student halls would be unlikely to be passed in suburban residential areas. So why, we ask, are residents in the city centre not given the same consideration?

“Sometimes these developments can inject life and investment into areas where regeneration of historic buildings are key objectives. But care needs to be taken over the impact on city centre living.”

Ultimately, though, in these straitened times, investment is king. And any developer with an eye for building a scheme, and a guaranteed supply of students from our universities is likely to push hard (and appeal, if necessary) against any objection.

“The market for city centre residential is less strong than student accommodation, but in planning policy terms, both are desirable. The trick is to make sure that one doesn’t compromise delivery of the other,” Grant adds.

“Action on anti-social behaviour is key. And we need to work with landlords under housing and licensing legislation, in partnership with the Universities and Student’s Union, to ensure action is joined up.”

So what of the Maghull Group? If you recall, it destroyed beyond repair the architectural details of Josephine Butler house (before and after pictures, right), before razing it to the ground completely. Although the building was eventually passed over for listing by English Heritage.

So what of the Maghull Group? If you recall, it destroyed beyond repair the architectural details of Josephine Butler house (before and after pictures, right), before razing it to the ground completely. Although the building was eventually passed over for listing by English Heritage.

Four years ago, LJMU came to a £10m commercial arrangement with Maghull Properties which saw Josephine Butler House and three other buildings in the Hope Street Quarter, including the the Hahnemann Building, site of the first homoeopathic hospital, and the School of Art, transferred to Maghull group

Four years ago, LJMU came to a £10m commercial arrangement with Maghull Properties which saw Josephine Butler House and three other buildings in the Hope Street Quarter, including the the Hahnemann Building, site of the first homoeopathic hospital, and the School of Art, transferred to Maghull group

The small patch of land on which it stood, at the corner of Hope Street and Myrtle Street, was the only non-conservation site in the Hope Street quarter (odd, when you realise that Josephine Butler House was the home of the first Radium Institute in the UK.)

When the Maghull demolition plans were made public, objections were made by heritage groups and local residents, and moves were made to have the building listed - supported by Liverpool Riverside MP Louise Ellman.

“There is already a thriving student population in the area,” their architects say, “and they contribute enormously to Hope Street’s cultural and commercial vitality.”

“We’ve been through a very detailed process with the City’s conservation and planning team and other heritage groups. We know the street well having designed the extension to Hope Street Hotel and other buildings in the area. Our architectural approach was therefore very respectful of location.”

They may well think that. You can see the building for yourself, above.

“The key is good management. There are good operators with experience and a proven track record and there are some companies who may be looking to cash in on what appears to be a lucrative market opportunity. Student Castle (the management company who’ll run the site) are a premium provider offering something that Liverpool needs if it is going to be able to compete to attract international students.”

“The key is good management. There are good operators with experience and a proven track record and there are some companies who may be looking to cash in on what appears to be a lucrative market opportunity. Student Castle (the management company who’ll run the site) are a premium provider offering something that Liverpool needs if it is going to be able to compete to attract international students.”

“Of course we need policies that safeguard quality and ensure good management, but we don’t believe there is anything intrinsically wrong with this location.”

For FCH and Maghull, the street, running right through Liverpool’s University and Knowledge Quarter, is a logical location. It’s hard to argue about its geography.

Merseyside Police say that student accommodation results in no corresponding spike in reports of anti-social behavoir. City Centre Neighbourhood Inspector Greg Lambert says: “Hotspots for things like anti-social behaviour, disorder and violence do exist but there are not any that are linked to the halls of residence.

“That’s not to say that students don’t cause a nuisance or commit crimes but overall they are more likely to be the victim of a crime like an assault or burglary than the offender.”

There is an established student community in Hope Street, and there is no history or suggestion of friction to date. Greg holds regular meetings with stakeholders where crime reports are analysed.

“There is just no crime pattern around student accommodation in the city,” he says.

At least, none that are reported to the Police. We mention our contributors’ tales of eggs on windows, footprints on Polos, and vomit in doorways.

“The problems you refer to about other areas in the City Centre point towards poor management,” FCH adds, “and maybe lack of care and responsibility by landlords and some students, but I don’t think anyone is suggesting that students are intrinsically undesirable or they are inevitably bad neighbours. It’s about management.”

Occasionally, in this city, the stars align perfectly. They’re shining down now, on Hope Street. Its recent award, its programme of year round family-friendly events, and its cultural (and gastronomical) power-houses are at the top of their game. The Street’s ecosystem has never been more finely balanced.

SevenStreets loves students. But we hate profiteering at the expense of the city we care about, live in, work in and champion. And we’d hate to see another short-lived ‘get rich quick’ gold rush for developers, scarring our city for the next generation, fleecing students and impacting neighbourhoods. A site this important needs an open competition - to deliver something truly befitting of its location.

Developers, Universities, Council - we have a suggestion: have you heard about the Baltic Triangle, there are thousands of ripe-for-development buildings there, not adjacent to residential properties. Go take a look.

» City Living » Halls of Resistance: Student City

34