All This Useless Beauty?

Have a guess how much empty space there is in Liverpool? No, really, have a guess - because no-one really knows. Nor does anyone know what to do about it. David Lloyd gets empty headed.

Somewhere deep in New Mexico, a desert full of hollows forms the Very Large Array telescope. Acres of discrete dishes. Insignificant alone. Game changing together. Working as one, the dishes can do something exponentially massive: map out the emptiness. Make sense of it.

It’s joined up thinking like this that edges us closer to the important questions - like, where the hell is all that dark matter? And what are we supposed to do about it?

Meanwhile, back in Liverpool we’re surrounded by the stuff. Imagine what we’d find if we embarked on a little joined up thinking of our own.

A few months ago, I started to wonder about empty spaces in the city, and of whether SevenStreets could hold an event in one of them. Within half an hour, a nice chap at the council suggested a few sites - probably about half a million square foot of them. Off the top of his head.

Nested within our city, hidden behind listed buildings, pedimented windows and stone mullions, just inches away from the lunchtime sandwich rush, there is a

Complete

Empty

City

“How many empty buildings are there, do you think?” we asked, our curiosity piqued.

No one seemed to know. Why would they? The council knows of its own empty spaces, individual developers and owners of theirs.

No-one has ever surveyed the complete shrinking city. We need to get Werner Hertzog and a laser scanner to map out the caverns and hollows, and make a complete 3D map of Liverpool’s empty belly.

In the meantime, forget about the Albert Hall. No-one knows how many holes it takes to fill up those grand, ghostly banking halls, fruit exchanges and typists’ pools.

While we wait, here’s an incomplete list of empty spaces: buildings either wholly empty or with upwards of 4,000 square feet lying fallow, waiting for the day when new seeds will be sewn. Some have plans. Most don’t. It’s a long list. You might want to break it up into bite-sized chunks.

Mersey House, Beetham Plaza

Tinlings Building, Victoria Street

Watson Building, Renshaw Street

Century Buildings, Brunswick

Churchill House, Tithebarn Street

1 North John Street

India Buildings, Water Street

West Africa House, The Strand

Queen Building, Dale Street

Colonial Chambers, Temple Square

Horton House, Exchange Flags

Oriel Chambers, Water Street

The Russell Building, School Lane

Granite Building, Stanley Street

Graeme House, James Street

Cunard Building, Waterfront

Littlewoods Building, Edge Lane

Albany (White Star), James Street

Royal Insurance (work is progressing), Dale Street

The Lyceum, Bold Street

Union House, Victoria Street

Produce and Fruit Exchange, Victoria Street

Eldon Grove, Vauxhall Road

Wellington Rooms (Irish Centre)

Tobacco warehouse, Stanley Dock

The Bank of England Building on Castle Street

Most of the north side of Lime Street

47 Castle Street

Temple Court

Fenwick Street building

Port of Liverpool Building, Waterfront

Victoria House, James Street

Compton House, Church Street

Bling Bling Building, Hanover Street

Scandinavian Hotel, Duke Street

And warehouses aplenty in the Baltic, and the docks.

At a conservative estimate, that’s over 8,000,000 square foot of space (the Littlewoods Building alone covers 600,000 sq feet), and the Tobacco warehouse 1,500,000.

And they wanted to close MelloMello? Are they out of their minds?

We don’t know exactly what this city needs. But we know one thing: it sure as hell doesn’t need another empty space.

Imagine for a moment what we could do with all that space if we looked behind the glossy images of our UNESCO Mercantile city. If we thought into the box instead of just salivated over its beautiful skin.

Trouble is, before you address a problem, you have to size it out. Capture it and proclaim it. Admit there really is a problem.

But figures like this aren’t, perhaps, what you want to hear when your Mayor believes that the city’s (only?) lifeline is an offer, from Peel, to build an entirely new city, just up the road and wait for Blue Chips to come and colonise. So much for our claim to be a city of green technologies. Where’s the big idea when it comes to recycling our existing stock of offices?

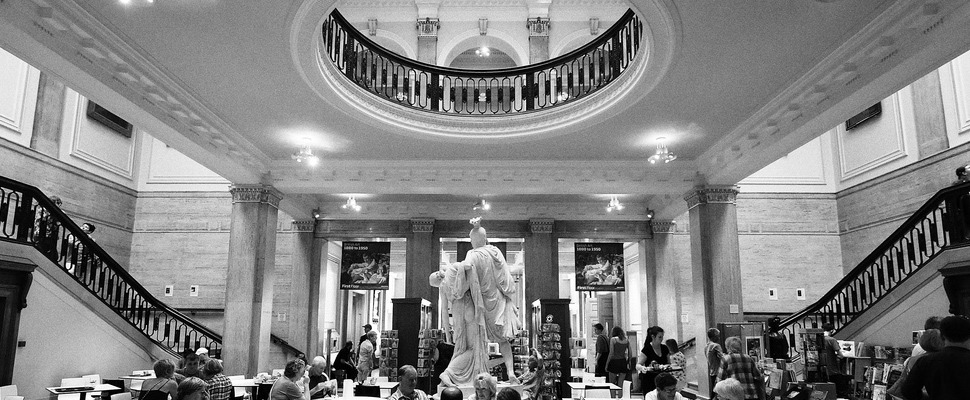

Now, of course, no-one is saying the grand corinthian pillars of the Cunard’s interior (currently holding up part of this year’s excellent Biennial) will suit a call centre (in fact, the space has been proposed as home for the new Migration Museum, but you get the point). But just because they’re not going to be used for IT support doesn’t mean they can’t have a purpose now. While we wait for the capitalist train to be put back on its tracks, here’s what should happen:

We need to rethink how we use our empty buildings. Get them to engage with each other. These buildings slip into the backdrop of our city. They become the great unseen.

SevenStreets suggests the city needs to appoint a Minister of Empty Spaces. That the city holds a Festival of Empty Spaces. That, for a couple of weeks, doors are flung open, and interested groups, individuals, societies, communities, schools, b-boy crews, knitting circles and guerilla fashion houses are shown around our sleeping city. And the best proposals are given the keys. Allowed to incubate. Infest us. Show us what we’re made of. Yeah yeah, there’s small print. There’s always small print. But that’s what we pay the public servants on Dale Street to sort out. Imagine if just 5% of this space was the catalyst for something incredible?

These buildings have good bones. They may, one day, make good offices, hotels, apartments (yes, homes: they’ve stood for 150 years. What’s the betting those empty, speculative, gangster-built shanty towns will last half as long?), and shops. But, right now, nothing is moving. And the recession ain’t going anywhere fast.

So let’s find a use for them. For us.

In Italy, they’re doing something about it. Impossible Living is an online inventory of empty spaces. Andrea Sesta, the driving force behind the site, explains:

“I want the site to help people with those ideas find sites that might fit their plans. We thought we could build a global container of these kinds of projects and help link resources with ideas, creating a community of people concerned about this problem and willing to do something about it,” says Sesta.

He’s hoping, too, that Impossible Living (not exclusively concerned with Italy, but mostly) will become a clearinghouse for resources and advice on transforming abandoned places.

“They are really difficult projects. They require a lot of expertise,” he says.

It’s happening elsewhere. In Berlin, decaying facades hide massive open spaces, full of artists’ workshops, studios and performance spaces. In Croatia, the summer is filled with temporary bars, clubs and event spaces. In Toronto, pensioners are learning to love the internet. In Paris, of course, entire soundstages are being erected for DIY feature films.

Here, Camp and Furnace has, spectacularly, shown what’s possible - with minimum budget and maximum passion.

But there’s more to life than parties. Which is why these spaces should be used for social enterprise too. Empty offices could turn into training camps: heck, we could even run a ‘how to write’ course (any takers?). We’d grab our students, take them to a gig at the Kaz, and bring them back to our sleepy hollow, and not let them leave until they’d found a new way to describe introverted Americana without using the words backwoods or Bon Iver.

Currently, the owners of these buildings pay full rates (unless they’re listed). Surely there’s sense in taking a gamble? Today’s free-use Saturday could be tomorrow’s Camp and Furnace, or multi-million generating bio tech company (the company that protected the Olympic park was set up in an empty corner of a plastic bag factory in Huyton. So it’s not all about the Vogue balls. Real, solid businesses grow from empty spaces too.)

London’s collective, This Big City has a ‘high-street hijack’ scheme, which takes empty buildings, and uses them to teach long-term unemployed new skills, without draining the already-stretched public purse too much.

When you think of our historic buildings, you realise they grew out of the town’s needs. Our grand buildings can do the same. They can resurrect us. Given half a chance and a little bit of vision.

We are a shriking city. The latest census results show that we’re being overtaken (especially in that crucial 25-45 age group) by every other core city. Meanwhile, Manchester fills its empty spaces with local food markets, and, in the only new empty space initiative we can think of, our council pushes through a ‘wet zone’ for alcoholics in the heart of the city’s night time economy, while a lone new puritan prowling the streets with a decibel reader leads the way in introducing Draconian new laws to prevent new uses for old buildings.

Removing the need for planning permission to temporarily change the use of empty buildings is key. As is removing the nay-sayers who’ll chirp health and safety. Most importantly, we need to do what we’ve always done best. Think differently. Take a leap of faith. Believe that the route out of here lies within us.

This christmas, Kate Stewart, the driving force behind the excellent Made Here shop in the Met Quarter is opening a selection of empty shops in the first ‘Pop Up for Christmas’ festival, showcasing the city’s makers and artists’ work.

It’s a great idea, and exactly the sort of thinking we need. But if we’re to really make a difference, we have to realise: pop ups aren’t just for Christmas. They’re for life.

» City Living » All This Useless Beauty?

13